Twisty Antiprisms

There’s an easy way to make antiprisms whose sides are isosceles triangles: take two congruent regular \(n\)-gons, rotate one so its vertices are halfway between the original positions (that is, by 1/(2n)-th of a circle), and lift one up. Unless you pick one particular height, you end up with isosceles triangles on the side. (There’s one height that gives you equilateral triangles.)

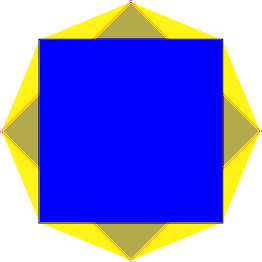

Here’s a top view of such square and pentagonal antiprisms (where the base faces are opaque but the triangles are transparent):

The base sides of each isosceles triangle are one of the sides of the base polygons, and the “up/down” sides are a different length. In fact, if the base polygon side length is \(b\), and the height between the two polygons is \(h\), the other sides are \(s = \sqrt{2 - 2\cos(\frac{\pi}{n}) + h^2}.\) Each vertex is in two edges of length \(b\) and two edges of length \(s\).

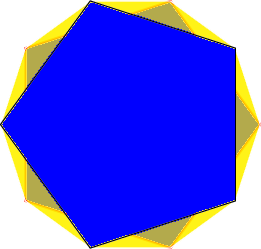

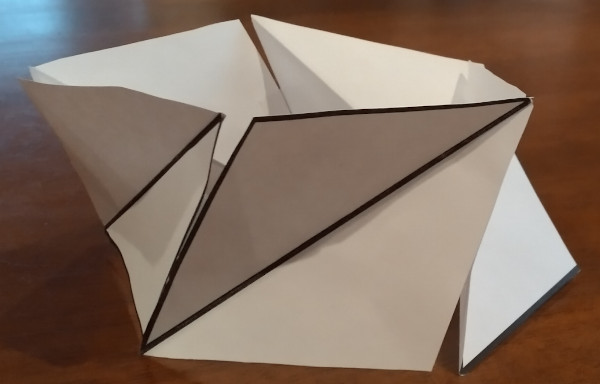

But I realized yesterday that there’s another way to arrange isosceles triangles around the side, so instead of the triangle’s base edge being on a base polygon, one of its two legs is on a base polygon. In each triangle, one of the edges joining the two polygons is scaled to match the base’s side-length \(s\), and the other one is a different length \(b\). Then each vertex is in three edges of length \(s\), and one edge of length \(b\), like this:

You do this by only twisting the bottom polygon a little bit with respect to the top one, so that one edge is short, and one is long. The top view is this:

However! We can’t make just any isosceles triangle the side of an antiprism in this way. (As opposed to the “usual” way, where you can get any isosceles triangle, by varying the height.) It only works if the ratio of the base to the leg is less than \(\sqrt{2}\).

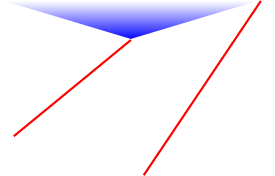

To see this, you can consider the creation of a twisty antiprism as starting from the uniform prism:

This has square sides; the length of the diagonal is \(\sqrt{2}\). Rotating the bottom slightly makes edge \(e\) get longer, and the diagonal \(d\) get shorter, and also breaks the square face into two non-coplanar triangles. The height between the base polygons can be reduced to make edge \(e\) have length one again—slightly shortening \(d\) also. Now we have a twisty antiprism; and the base length is shorter than \(\sqrt{2}\).

Continuing the rotation keeps shortening \(d\) until we achieve equality, right when we’ve rotated halfway to the next vertex. If we keep going we can have the base side be shorter than 1, and it gets arbitrarily short as we rotate nearly to the next vertex (and the two bases nearly come together).

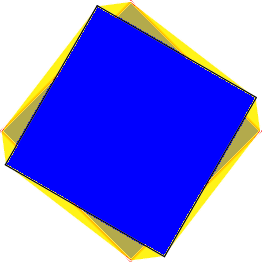

So, this argument shows that wider isosceles triangles won’t work: but what actually goes wrong? I tried to construct one with isosceles triangles whose base is the golden ratio, \(\phi\), of the legs. The golden ratio is larger than \(\sqrt{2}\), so it didn’t work: in fact the triangles buckled in, so the result was not convex.

This came up when I was thinking about vertex-transitive 4-dimensional polytopes whose facets are all equilateral pentagonal pyramids. It turns out the vertex figure of such a beast would have to be exactly that: a pentagonal twisty antiprism with base sides of length 1 and diagonals of length \(\phi\).

Since there’s no such thing, there’s also no vertex-transitive equilateral 4-polytope made of pentagonal pyramids.